Things fall apart. Is that bad or good?

Cookies crumble in 'Lehman,' 'Alma,' 'The Play You Want', 'Hooded,' 'Trayf', 'Apartment Living,' but 'On the Other Hand'...

Drama often depends on dissolution. If a script were to depict best-laid plans that didn’t go awry, we would probably be bored.

Of course, this phenomenon extends far beyond the stage. A lot more Americans are paying attention to international news lately, because the drama of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the hope for an ultimate collapse of the Putin regime feel so urgent.

Most of the recent plays I’ve seen in Los Angeles are structured around a process of disintegration. Of course they aren’t on the level of the latest bulletins from the theater of war, but many of them are nonetheless compelling in their own, more measured ways.

To begin with the most obvious, look at “The Lehman Trilogy,” at Center Theatre Group’s Ahmanson Theatre. It’s a saga about the giant Lehman Brothers investment bank, which famously collapsed in 2008, in a key “Great Recession” moment.

The bank’s origins are less familiar to most Americans. They began with three German Jewish brothers who arrived in America in the mid-19th century. But even then, unplanned disruptions regularly upset the narrative. Henry Lehman, the oldest and first of the brothers to arrive, died of yellow fever at the age of 33. The Civil War almost literally torched the two remaining Lehmans’ Alabama-based company, which initially relied on cotton.

“The Lehman Trilogy” was created by the Italian writer Stefano Massini and adapted into a more-than-three-hours trilogy by Ben Power for a British production by the National Theatre. In the age of streamed multi-episode TV series, it’s unusual that a story on this scale first appeared on the stage instead of the screen. It was less surprising when the news broke late last year that an Italian company now plans to adapt it into, yes, a TV series.

A much longer TV series would be able to tell this lengthy story more thoroughly. A lot of unanswered questions linger after seeing “Lehman” at the Ahmanson. What specifically caused the brothers to immigrate? Was antisemitism a factor — in Germany, Alabama, or New York? Why did they start their business in the South, so far from most of their fellow immigrants? Should there be more than one brief speech in which it’s pointed out that slavery was essential to their initial fortune? Why is there no mention that they actually owned slaves?

The tales of the founders’ successors, within the family and the company, feel rushed and even less comprehensive in “The Lehman Trilogy.” But at least the script notes that the gradually diminishing role of Jewish observance in the Lehman family accompanied their gradually increasing devotion to dealing in money, as opposed to tangible goods, in their business (see also my comments on “Trayf,” below).

The saving grace of the trilogy, directed by Sam Mendes, is the stagecraft. Three men play all of the roles in the entire saga (although a few other actors occasionally appear as other people anonymously, without speaking any lines). These three play women as well as men and often venture outside their natural age ranges.

Two of the original cast members, Simon Russell Beale and Adam Godley, are here, and Howard W. Overshown has now joined the trio. Much of the gee-whiz quality that keeps us interested for more than three hours is derived from the actors’ amazing versatility. Our sustained interest also owes a lot to Es Devlin’s scenic design, focusing on a transparent box that shifts into a series of striking angles, backed by sometimes breathtaking video designed by Luke Halls.

Is ‘Alma’ ‘The Play You Want‘?

“Lehman,” at CTG’s biggest space, confirms CTG’s status as the company that most often brings us prestigious international drama. Meanwhile, CTG’s Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City, its smallest space, has re-opened with the premiere of Benjamin Benne’s “Alma” — which appears to mark a welcome dedication to new plays that not only are by local writers but also are set in greater Los Angeles.

I use the phrase “greater Los Angeles” because “Alma,” by Benjamin Benne, takes place in the city of La Puente, which is a municipality that many Angelenos who attend theater in Culver City probably know nothing about. It’s a city with a population of about 40,000, mostly Latino, about 20 miles east of downtown Los Angeles.

In contrast to the scale of “Lehman,” “Alma” is very small. It’s set entirely in one apartment, occupied only by the the title character (Cheryl Umaña), an undocumented immigrant from Mexico, and her daughter Angel (Sabrina Fest), who was born in the US and is now approaching her high-school graduation. No father, or any other character or setting, is part of the play.

Angel has decided not to take SAT the following day, much to Alma’s chagrin. The play consists mostly of their argument, in real time, about this dissolution of Alma’s dream for her daughter.

For some insufficiently explained reason, the only college under discussion for Angel is UC Davis, in northern California, even though there are many UC and Cal State campuses and even private colleges that might offer Angel a scholarship, as well as community colleges, within 30 miles of La Puente. Near the end of the play, we understand why a college with a greater distance from their apartment was a useful dramatic device for Benne, the playwright, but it’s a very artificial restriction for these two characters.

Nonetheless, the play does achieve a degree of familial poignance and also has moments of political commentary — although, because it’s set in 2016, the commentary feels a bit stale.

Unfortunately for “Alma,” it opened during the same weekend as Bernardo Cubría’s “The Play You Want,” a satire that makes fun of plays along the lines of “Alma.”

At the Road in North Hollywood, “The Play You Want” depicts a Mexican-American playwright with the same name as the Mexican-American Cubría himself. This (supposedly fictional) Cubría would like to write plays about topics that aren’t necessarily Latinx flavors of the moment, that don’t necessarily feature undocumented immigrants or the Day of the Dead. For example, he likes plays about clowns. The real Cubría wrote one of these, “The Giant Void in My Soul,” which many of us appreciated in a 2018 production.

But the Cubría (Peter Pasco) in “The Play” finds that his only suggestion for a script that will interest Oskar Eustis, who runs the Public Theater in New York (and who was a CTG associate director from 1989 to 1994) — is “Narcocos,” an idea pushed on him by his agent after Cubría generated it in a throwaway moment of sarcasm. As the momentum grows for “Narcocos,” his self-esteem sinks even as his income inflates.

Much of “The Play You Want” is very funny, especially for inside-theater fans. The script doesn’t shy away from using the real names of the theatrical and Latino celebrities who board the “Narcocos” train. It might seem even more daring at the Road if it were set in LA and mentioned current real-life LA figures.

“The Play” also has a soft underbelly. The fictional writer’s wife (Chelsea Gonzalez) is growing impatient with the habitual problems of his chosen profession, and they have a two-year-old son whose preschool wants a lot of money. The boy is played by a puppet (its designer: Lynne Jeffries) and the performances — including the puppet’s — are razor-sharp.

The production’s director Michael John Garcés (who’s also the artistic director of Cornerstone Theater), the Road and Cubría turn “The Play You Want” into a play that, yes, we want.

‘Being Black’ in ‘Hooded’, being Chabadnik in ‘Trayf’

While “Alma” and “The Play You Want” display two very different types of Latino characters whose dreams are dissolving, “Hooded, or Being Black for Dummies” introduces two disparate types of young African-American characters going through changes, all within one script. Echo Theater Company is presenting the local premiere in Atwater.

Playwright Tearrance Arvelle Chisholm threw together Marquis, a kid (Jalen K. Stewart) who was adopted by a wealthy white mother and is now attending a mostly white prep school in “Achievement Heights, Maryland,” and a much less affluent teenager, Tru (Brent Grimes) from the streets of Baltimore.

They meet in a holding cell after Marquis and two white classmates were arrested for trespassing in a cemetery, although the two white guys escaped the long arm of the black arresting officer (Robert Hart).

Marquis is more formally educated than Tru, to the extent that one of his chosen conversational topics is Apollo and Dionysus — and Chisholm decided that these Greek gods should make a few appearances in the play. Marquis also is a fan of Nietzsche, but he doesn’t know much about “being black.” Tru decides to tutor him, guided by the words of 2Pac.

According to the script, Marquis, Tru and all of Marquis’ classmates are 14. But in Ahmed Best’s staging they all seem about three or four years older — approximately the same age as Angel in “Alma.”

The script has too many distracting gimmicks at the beginning. But these moments also serve to introduce “Trayvoning,” a social-media phenomenon of which I had been blissfully ignorant. Within a year after the fatal shooting of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in 2012, some teenagers, often white, posed on sidewalks in photographed imitations of the way Martin’s body looked after George Zimmerman shot him — and then sent these images out to their friends. Advance knowledge that “Trayvoning” was a real thing might help spectators as the play proceeds through edgy comedy to a surprisingly powerful ending.

While “Hooded” emphasizes that it’s important for young black men to know about the current rituals of “being black,” playwright Lindsay Joelle has a very different perspective on cultural identity in her “Trayf,” at the Geffen Playhouse. She suggests that excessive devotion to the specific customs of one’s demographic group can also cause friendships to crumble — if your best friend has a more open view of the world than you do.

In 1991, the young New Yorkers in “Trayf” live within a Chabad sect in Crown Heights (before their revered Rabbi Schneerson’s death in 1994). Pals Zalmy (Ilan Eskenazi) and Shmuel (Ben Hirschhorn) initially appear to be equally observant, but their conversations with a new devotee (Garrett Young) reveal a greater tolerance for the outside world in Zalmy than in Shmuel.

The performances in Maggie Burrows’ staging uncover a lot of pain in this process, but Joelle ultimately seems to believe that Zalmy will be better off as a result of his transformation — in stark contrast to the conclusion in “The Lehman Trilogy” (see above) that the deterioration of religious observance accompanied the worst excesses of capitalism.

Joelle’s script is less cluttered with extraneous business than Chisholm’s. But as in Chisholm’s play, Joelle’s two central characters seem to be cast somewhat older than their announced ages.

Of course living within any carefully controlled culture is an exotic concept to many Angelenos — especially those who live in multi-unit dwellings, where the idea of choosing your neighbors is usually not an option, even if you’re so inclined. I hoped that “Apartment Living,” a Playwrights’ Arena and Skylight Theatre production at the Skylight in Los Feliz, set in LA during the early COVID era, might have something to say about all of that. I also hoped that it would offer insights on LA’s particular communal experience of the past two years.

Boni B. Alvarez’s script includes one character who contracts COVID. But this character isn’t essential for the play’s narrative engine, in which a man who’s engaged to be married to his female roommate is also having furtive sex with the young man who lives next door. This whole affair seemingly remains a secret from most of the characters even by the play’s end. “Apartment Living” needs to show more of the drama of dissolution — and disillusion.

Another trio of actors, but in close-up

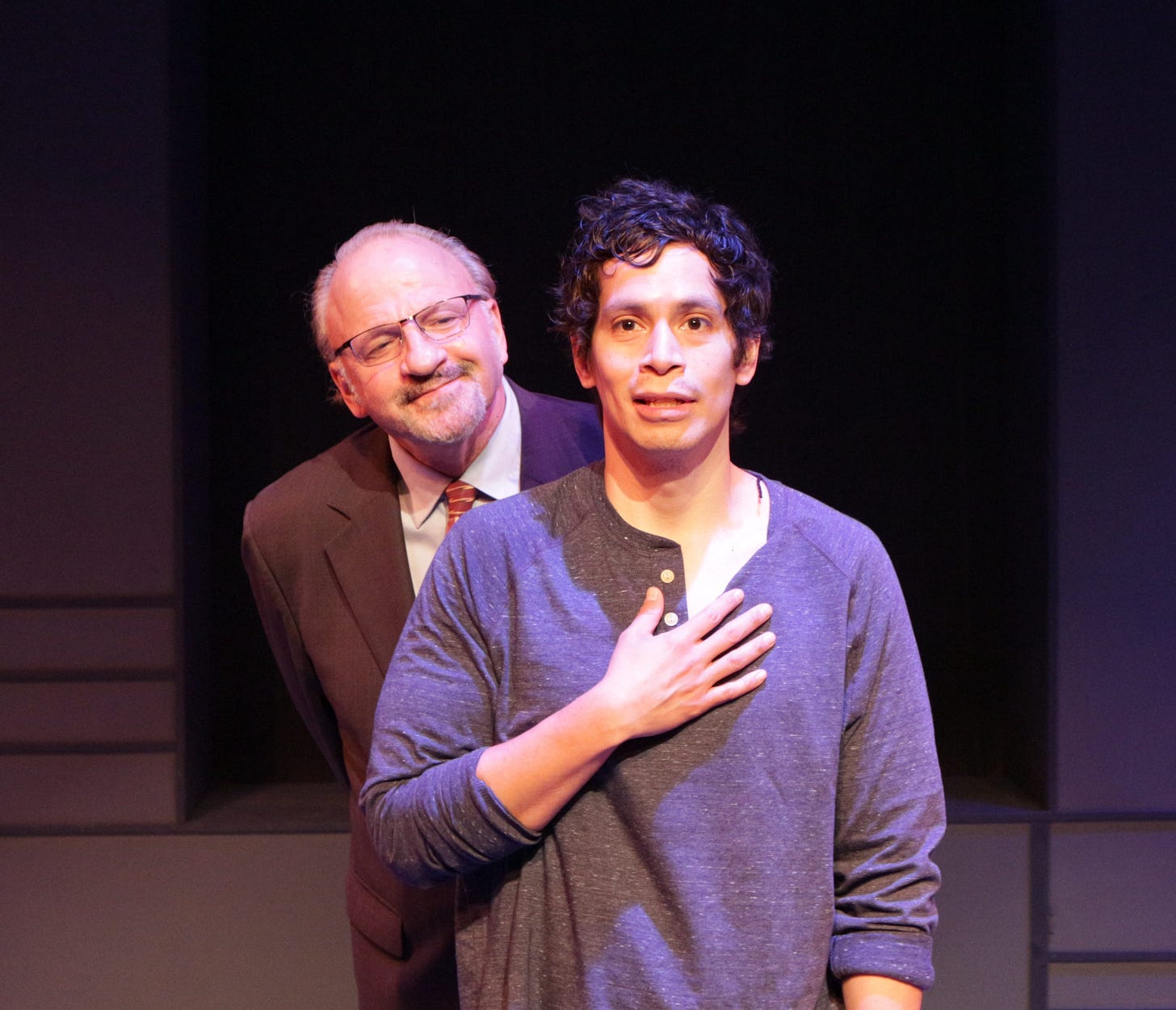

Some readers will feel that I’ve saved the best — “On the Other Hand, We’re Happy” — for the last. In this US premiere of Welsh writer' Daf James’ play at the Matrix Theatre on Melrose, we return to the “Lehman Trilogy”s technique of having only three actors play all of the roles. But here it’s on a miniature scale, in a masterful in-the-round staging by Cameron Watson for Rogue Machine, whose production brings us closer to these characters than we could ever get to the Lehman Brothers.

For the sake of not giving away spoilers. I won’t say much about the plot of this play except that it’s about a couple who want to adopt a child in the UK. But based not only on my experience at a particular performance but on what I’ve read and heard from others, I’m quite confident that almost anyone would be moved by this tale and by the trio that performs it — Rori Flynn, Alexandra Hellquist and Christian Telesmar.

Yes, James seems to say, at least some of us endure unexpected trauma but still return to a form of happiness. At this point in our history, who could ask for anything more?

A sign of life at the Colony

It’s great that actors are again performing in Burbank’s Colony Theatre, because the space itself is one of the best midsize theaters in greater LA. I can’t endorse the current “The Revue,” which is structured around the misbegotten idea of doing musical parodies of content from far too many sources, many of which are movies that I never saw or long ago forgot. But at least “The Revue” is using the estimable skills of Troubies Matt Walker as the onstage “director” and Rick Batalla as the onstage “producer,” as well as a skilled mostly-non-Troubie case of four. And its troubled concept reminds us of why the Troubie style of satirizing particular plays or celebrities in depth usually amuses theater audiences a lot more than this movie-blockbuster-centric material would. Now, if only some angels could help the Colony company itself, or a successor, recover from its 2016 collapse, its own drama of dissolution might not seem so dismal.

.