Should plays imitate TV? Bill Bushnell, R.I.P.

'One of the Good Ones,' a savory 'Stew,' 'The AllStore,'and the late LATC leader

“What is your hope for ‘One of the Good Ones’ after this run ends?”

Gloria Calderón Kellett was asked that question in an LA Times interview about her new play “One of the Good Ones,” currently at the Pasadena Playhouse.

Her answer began with these words: “Whether it’s a pilot or a play, I always love putting up new work…I would love to keep developing it at other theaters, and I’m hopeful that it will lead to audiences’ conversations, healing and understanding of one another.”

I immediately began pondering the word “pilot” at the beginning of that answer.

After all, Calderón Kellett is best known as a TV showrunner. The first paragraph of her bio in the Playhouse program cites three TV series that she ran or runs in some function — but the bio mentions no theater credits (although she apparently acted and wrote with small LA stage companies Chalk Repertory and Elephant Theatre, in the pre-COVID era). In 2020, the Geffen Playhouse honored her and Diane Keaton at an online “Backstage Live at the Geffen” fund-raiser — also with no mention of any stage credits in the promotional materials about the event. Calderón Kellett has offered online pilot-writing classes.

Could “One of the Good Ones” be a TV pilot as well as a play?

In Charles McNulty’s review in the LA Times, he didn’t directly ask that question, but he did refer to the play as “a theatrical comedy in the sitcom tradition of Norman Lear,” the great TV producer who received a glowing tribute from Calderón Kellett herself in the Times soon after Lear died in December.

Watching the play, I noticed that the nuclear-family configuration here was somewhat similar to the initial premise of Lear’s trailblazing “All in the Family”: a grouchy dad, a fluttery but good-hearted mom, their young-adult daughter and her new boyfriend who annoys the dad.

Major differences also exist. “One of the Good Ones” is about wealthy Pasadenans from varying Latine-American ancestries, while “All in the Family” was about a lower-middle-class white household in Queens (New York City). Archie Bunker would have been suspicious of all of the characters in this play.

Still, the dad in this play is suspicious of the “white”-appearing boyfriend, even though the younger man was born in Mexico and speaks better Spanish than the dad’s own wife. In fact, the play uses the sitcom format largely to explore the complications — and sometimes the lack — of cultural identities in contemporary culture.

It also explores women’s roles in a way that “All in the Family” didn’t. The mom has an active career and doesn’t prepare dinners — other than the salad. The 22-year-old daughter, who has just graduated from college with honors, is a “patriarchy”-criticizing influencer — but she also has made two surprising decisions that feel somewhat inconsistent with her previously expressed attitudes and therefore unlikely (I can’t be more specific without revealing spoilers).

I admire Lear’s sitcoms. They discussed similarly topical subjects. But the straightforward style of their presentation was appropriate in millions of living rooms, not theaters. The theatrical experience often takes more imaginative risks than the TV sitcom experience, as Pasadena Playhouse demonstrated with its last mainstage production, “Kate,” which clearly belonged in a room, live, as opposed to a pre-recorded TV screen. Furthermore, the 643-seat Playhouse itself is too big for live TV sitcoms. I missed a few words here and there because I was seated rather far from the stage, and laughter from other spectators sometimes obscured subsequent lines.

I appreciate that “One of the Good Ones” is set specifically in Pasadena, not far from the site of its premiere, and that its characters are affluent Latines — less commonly portrayed than less affluent Latines. Kimberly Senior’s staging is efficient and Tanya Orellana’s set is impressively handsome. I laughed out loud maybe a half-dozen times.

But I won’t be surprised if it’s been converted into a TV version within a few years. It might even get a better title than “One of the Good Ones” (huh?), which is too close to the title of Calderón Kellett’s best-known credit — the streamed remake of Lear’s original TV series “One Day at a Time.”

‘Stew’ in a smaller pot. ‘AllStore’ —a black-box big-box

Last August I wrote that the Pasadena Playhouse was also too big for the LA premiere of Zora Howard’s “Stew,” which needed “a smaller pot.” Well, Ebony Repertory Theatre is currently providing that smaller “Stew” pot in its 399-seat home at the Nate Holden Performing Arts Center on LA’s West Washington Boulevard, a few blocks northeast of La Brea and the 10 freeway.

It’s a much tastier concoction. Beyond the venue’s relative intimacy, credit also goes to director Jade King Carroll and the quartet of actors led by Greta Oglesby as a harried Mama preparing a stew, Roslyn Ruff as her older daughter Lillian (Ruff played the same role in Pasadena), Nedra Snipes as Mama’s younger daughter and iesha m. daniels as Lillian’s daughter. Lindsay Jones’ sound design is harrowing in the final scene, even though the playwright never spells out exactly what is happening. This improved “Stew” closes on Sunday.

Looking for a brand-new play that “takes more imaginative risks than the TV sitcom experience” (I’m quoting myself, from five paragraphs ago) and also has moments when the writer isn’t clear about what exactly is happening, even more so than “Stew”? Try shopping at “The AllStore,” by Evan Marshall, at Theatre of NOTE in Hollywood.

The setting is a big-box store. I’m aware that this might sound like the sitcom “Superstore,” which was on NBC from 2015 to 2021. No, I haven’t watched all 113 of the sitcom’s 22-minute episodes.

Still, I’m quite confident that “The AllStore” feels more like theater and less like, well, a sitcom than any single “Superstore” episode. Its running time is well past an hour, not 22 minutes. And of course the actors are live, a few feet away from us, in a small black-box space that nonetheless suggests a big-box store quite effectively — if only as a sketch —in Colin Lawrence’s set design.

But the biggest difference is in the dialogue, which occasionally rejects realism in favor of heightened modern-verse passages, usually spoken by the 20-year-old clerk Petra, who is studying poetry at college. Dreams also are enacted — for example, in one of them, the founder of the company visits one of the frustrated employees (probably from the grave?). These elements serve to momentarily lift these characters out of their humdrum work experience and provide them with a degree of audience empathy that might exist only after, say, 20 episodes of “Superstore.”

Don’t worry — “The AllStore” still gets laughs, and its dramatic conclusion leaves us wondering what happens next, as in a good TV series. But to provide the answer to “what happens next” is logistically more difficult in theater than in a TV series. And perhaps it’s more fun for us to imagine the future scenarios within our own minds.

By the way, two of the roles in “The AllStore” are cast with alternating actors, and at the performance I saw, “swings” appeared in two other roles — including the playwright himself, Marshall, in the double role of brothers Blake and Blair. So don’t expect comments from me on the performances of whichever actors you might or might not see at “The AllStore.”

Brash Bill Bushnell

I was startled last week to notice an online article from americantheatre.org that was an “in memoriam” tribute to Bill Bushnell, by one of his former colleagues Lisa Mount. I didn’t know that Bushnell, one of the most important theatrical impresarios of LA theater in the past half-century, had died — on January 31, at the age of 86, in Cuenca, Ecuador.

I quickly looked at latimes.com to read what I assumed would be a detailed LA Times obituary that I had somehow missed, and found — nothing.

Bushnell was the dynamo who opened and ran the original Los Angeles Theatre Center, in the building still known as LATC, on Spring Street in downtown LA. From 1985 until 1991, LATC rivaled the nearby Center Theatre Group (at the Music Center) as a hub of LA’s vast non-profit professional theater scene

After previous jobs at non-profit theaters in Cleveland, Baltimore and San

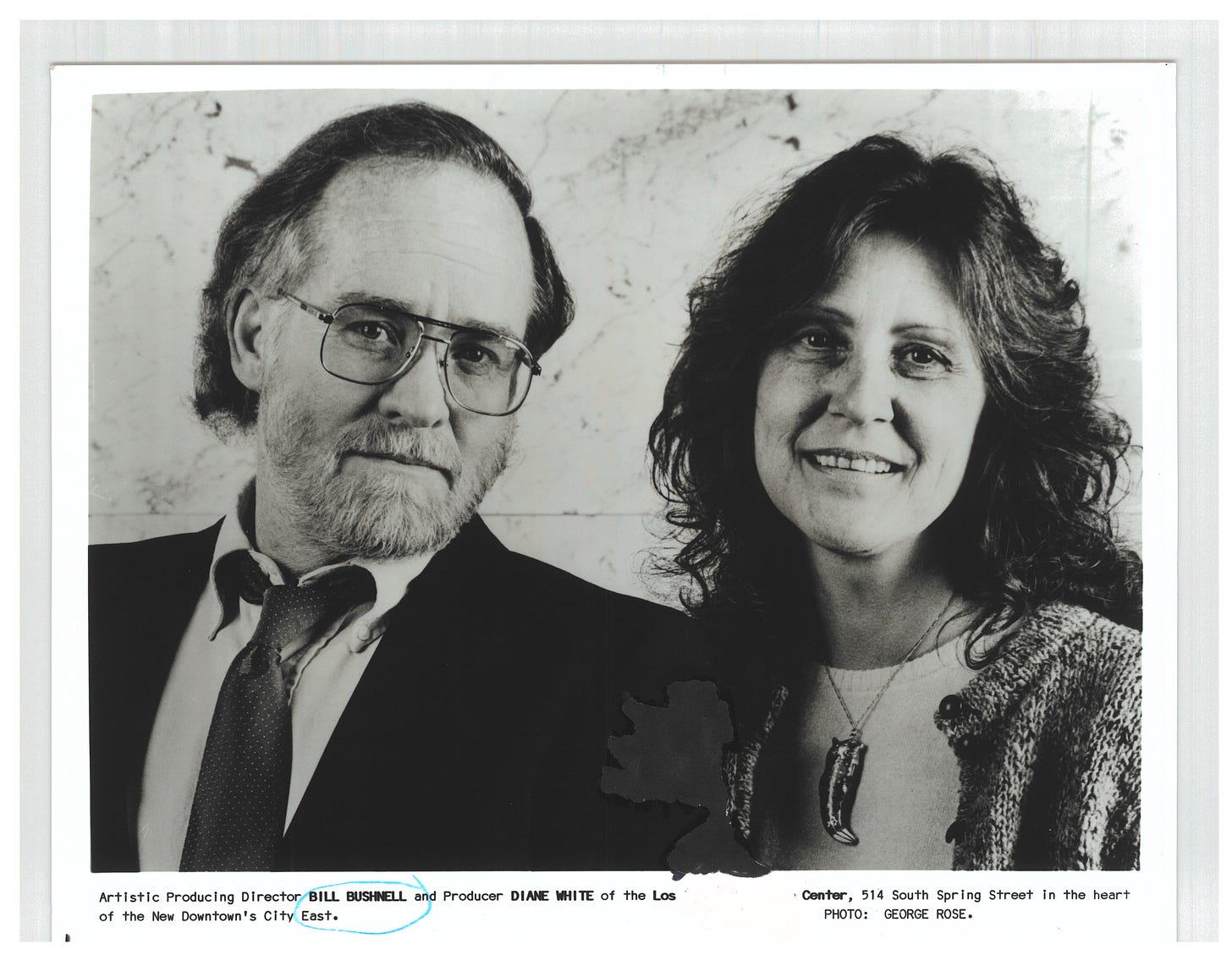

Francisco, “Bush” — as associates frequently referred to Bushnell — migrated to LA. He joined the Los Angeles Actors’ Theatre (LAAT), a small company that the actor Ralph Waite had founded in the 1970s — and Bushnell eventually took charge of it. It was located in an east Hollywood building (which was recently re-named the Eastwood Performing Arts Center) on Oxford Street, just south of Santa Monica Boulevard. Then LAAT morphed into LATC when the Spring Street building opened in 1985, in what was then called the New Downtown’s City East (see photo, above).

The LA Times was well aware of Bushnell and LATC back then. The newspaper’s theater critic Dan Sullivan opened his article “The Theater of the Brash Makes It Big” on the eve of the LATC opening with these words:

“A subscription brochure for the new Los Angeles Theatre Center quotes Diaghilev’s famous exhortation to Nijinsky: ‘Astonish me!’ LATC has astonished us already. From a small rented theater in Hollywood to a new $16-million downtown arts complex in only 10 years — it’s an audacious leap.” He compared LATC’s four venues (three midsize, one 99-seat) to those of New York’s Public Theatre, suggesting that Bushnell might become LA’s version of Joseph Papp — both were non-profit producers who knew how to get big things done without necessarily playing it safe, artistically. Two years earlier, Sullivan had written a brilliant profile of “Bush: 'Operator,' Genius, Maverick, an Inspiration,” which I recently re-read using the LA Public Library website.

Of course most LA theater fans who were adults in 1991 know that Bushnell’s dream collapsed that year, crushed by mounting debt. However, Latino Theater Company, which was born under LATC auspices during the Bushnell era, began producing regularly at LATC in 1996 and took over management of the building in 2006 — although it hasn’t maintained the pace of productions that were staged there during the Bushnell years.

In 2003, I interviewed Bushnell for the Times as he visited LATC for the first time since he left. He described his post-LATC adventures on a boat in the Virgin Islands, followed by his work for FEMA’s hazard mitigation department. “I had perfect training for working on disasters — 35 years in the theater,” he said. “I know how to talk to city officials and middle-management engineers.” Yet he had returned to LA briefly to direct a play at a small theater in NoHo.

Bushnell was a recovered alcoholic, and I ended the article with his comment that emotionally, he still felt as if he were 27 — the number of years that he had been sober — “and I’m going to live to be 128.”