Designs for 'Living', for a premie, for making old Hollywood more 'Chinese.'

Abe and Mary sing! Bye-bye 'Planet Earth.' 'The Outsider.' Putin's plans for playwrights.

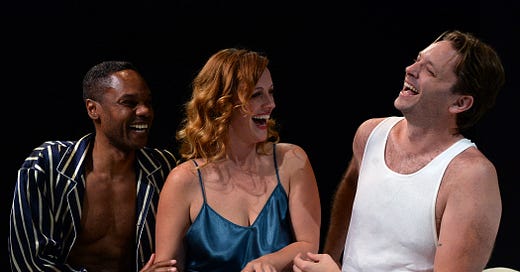

As Noel Coward’s “Design for Living” ends, gales of laughter erupt from the two men and one woman who have finally realized that they’re meant to be a ménage à trois. The audience joins in — the laughter, that is. The Odyssey Theatre in West LA is currently producing a delicious revival of Coward’s seldom-seen 1932 comedy

Meanwhile, these days we’re hearing a lot about the Project 2025 manifesto, written by many of Donald Trump’s advisors, revealing their hopes for a Trump presidency. "Married men and women are the ideal, natural family structure” according to the Project. The government would "maintain a biblically based, social science-reinforced definition of marriage and family." Perhaps it’s no surprise that the thrice-married, twice-divorced Trump, recently convicted of falsifying business records in connection with his extramarital alliance with an adult film star, is now pretending that he knows almost nothing about Project 2025.

These ironies are rich enough that the three protagonists of “Design for Living” are probably enjoying them with more howls of laughter in the afterlife. I hope that they can somehow experience the Odyssey production, consummately staged by Bart DeLorenzo (who notes in the program that Coward completed writing the play “as his boat waited to dock in Los Angeles”).

Surely budding playwright Leo (Kyle T. Hester) would be impressed by Coward’s craftsmanship. Fledgling painter Otto (Garikayi Mutambirwa) and the woman who is drawn to both of them, designer Gilda (Brooke Bundy), also would be delighted. The three leads have a terrific chemistry, and the production also features plucky and droll supporting performances from Sheelagh Cullen in two roles and from Andrew Elvis Miller as the resident spoilsport.

Please show us your baby photos

Although the adults-only world of “Design for Living” appears to be in a different solar system from a contemporary neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), a NICU is also designed for living. It’s where premature and/or ill newborn infants who need specialized care stay for weeks or even months so that they can live.

At first Mike Lew’s NICU-set “tiny father,” directed by Moritz von Stuelpnagel at Geffen Playhouse, is absorbing, almost in the manner of a documentary — but with one big difference. In this production, we don’t see any images of the infants themselves.

Instead, the play is about the plight of an American man (Maurice Williams) who’s shocked to discover that his brief and casual encounter with a Japanese immigrant resulted in a very premature infant — and then that the woman herself died soon after giving birth, leaving him as the sole surviving parent of a child in an alarmingly precarious condition.

Keeping the mother unseen from the get-go struck me as somewhat contrived — and it eliminated some of the potential drama. Instead the only other character on stage is the night nurse (Tiffany Villarin). Perhaps Lew was too attached to his play’s title? I prefer his comedy “Tiger Style!,” seen two years ago at SCR.

However, after seeing “tiny father,” I learned that Lew, in his preface to his script, included a suggestion that a producer or director might want to include “photos of a real-life NICU baby tracking their development” in the design. From the transcript of an interview with Lew on the Geffen website, I also learned that he and his wife (no, he’s not a single father) have been through the NICU experience twice. Better yet, the webpage includes a photo of Lew with one of their tiny infants, looking up at Dad. That photo instantly raises the emotional stakes of the NICU experience in a way that the production itself does not. The production closes Sunday.

Chinoiserie — D.W. Griffith style

If you mention film pioneer D.W. Griffith, most people will think first of his landmark 1915 epic “Birth of a Nation” — not only for its groundbreaking cinematic achievements, but also for its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan. Griffith, the son of a former Confederate soldier, tried to make amends for the latter problem with his next epic “Intolerance” and then with the more intimate “Broken Blossoms” (1919), in which he depicted a tender relationship between an older Chinese man and a white girl who has been abused by her father. Among Griffith’s efforts was a change in the title from the original story’s title (gulp), “The Chink and the Child.”

Griffith apparently didn’t think twice about casting a white movie star, Richard Barthelmess, as a Chinese man wearing “yellowface” makeup — or casting 25-year-old Lillian Gish as the possibly pre-teen girl. However, he did hire two Chinese immigrants as consultants, primarily to help Barthelmess feel more comfortable in his role.

The premiere of Philip W. Chung’s “Unbroken Blossoms” at East West Players in downtown LA is a fascinating excursion into this seldom-discussed episode in the history of Hollywood racism. Chung has written the older consultant, Moon Kwan (Ron Song) as a polite but more assertive character at first, while his colleague James Leong (Gavin Kawin Lee) advocates simply smiling and nodding to whatever Griffith (Arye Gross) or anyone else says — because Leong wants to use his consultant gig to advance his own training and connections as a would-be film director.

Chung describes his play as “a work of fiction” in a program note, and the fiction kicks into high gear in a subplot that embroils the main characters, who were indeed real historical figures, in incidents that apparently never happened (after you see the play, if you want to know more about what is fictionalized, you might begin here).

Both Alexandra Hellquist, whose primary role is Gish, and Conlan Ledwith, whose primary role is Barthelmess, play additional secondary roles — but I was never confused, which can easily happen when actors play two roles. Ledwith is especially effective in creating laughs as the fictionalized (indeed, caricatured?) Barthelmess.

Chung’s fictional narrative twists help drive the drama, as does Jeff Liu’s direction. And these moments build Lee’s role into a more complex character, enabling him to justifiably take the final bow during the curtain call.

‘The Lincolns’ of Burbank

Speaking of D.W. Griffith’s Confederate-family roots, earlier this year I read and enjoyed historian Doris Kearns Goodwin’s epic book “Team of Rivals,” which relates how Abraham Lincoln and his previous political rivals designed the eventual re-unification of the United States after the end of the Confederacy. So when I heard about a new musical titled “The Lincolns of Springfield,” at the Colony Theatre in Burbank for only two weekends (closing this Sunday), I was eager to see it.

The musical covers almost as many years as the massive book, but in a standard musical length of between two and three hours. Because of my recent reading, I could compile a long list of what was left out.

Terrence Cranert — who wrote the book, music and lyrics and also directed — created 14 of his own musical numbers plus one reprise. Many of them fall into standard cliches — the titles include “Dream, Hope, Pray,” “Over Yonder” (which is the song that receives a final reprise), “When You Love Someone” and “Together Me and You.”

Others feel oddly off-topic. In “Someone Who’s as Good as General Lee,” Mary is completely absent while Lincoln and his team of rivals (though Cranert avoids emphasizing their former rivalry) sing about which Union generals might win the final victory, with no mention of the general who later turned out to be the answer to that question — Ulysses Grant. The orchestral sounds behind the singing were pre-recorded.

The musical highlight might well be “Freedom,” a slaves’ chorus at the beginning. But generally the singing and dancing can’t match the simple eloquence of Lincoln’s own Gettysburg Address, which Lincoln (Garret Deagon) delivers word for word. Deagon smoothly makes the transition from a tall, dark and handsome young man (it’s a little hard to believe that other characters disparage his looks) into the president who saved the Union in his 50s. But the role of Mary Todd Lincoln (Samantha Craton) isn’t particularly developed beyond the predictable.

Lincoln’s leadership skills could be inspirational in our currently divided nation. For example, if President Biden were to change his mind about letting someone younger take charge of the Democratic ticket, a “team of rivals” attitude would be very helpful. But it might be more useful for anyone to read more about the first Republican president than it would be for them to see a musical comedy about him.

Since I just turned the topic to politics, I want to take note of a couple of now-closed productions (which I saw since my last post) that might deserve longer lives in other venues, as we draw closer to the election.

“The Planet Earth Farewell Concert” was part of the Hollywood Fringe Festival. Jonas Oppenheim’s original and clever musical-comedy revue about climate change took on a depressing and seemingly insoluble worldwide crisis in a way that might engage those who have stopped reading serious articles on the subject. Amanda Blake Davis was especially amusing in the title role.

Although I certainly enjoyed the “Concert,” its attitude on fighting climate change via the real-life electoral process was a bit limp. After all, in April Trump reportedly offered to scrap most environmental regulations if fossil-fuel executives would give his campaign $1 billion. Certainly such a brazen bribery solicitation should have been highlighted in a satirical revue about climate change a few months later.

International City Theatre in Long Beach presented the West Coast premiere of “The Outsider,” Paul Slade Smith’s mostly funny satire about a small-state policy wonk/lieutenant governor who is suddenly thrust into the limelight when the governor is forced to resign. Consultants try to re-make the new guy (Stephen Rockwell) into more of a people pleaser.

The play was introduced in 2015, so it has no direct ties to today’s political climate, other than its position that totally unqualified candidates can win supporters for completely irrelevant reasons. The play’s outer ring of satire involving an office temp — who may in fact be the title character? — struck me as too over-the-top. The play is not to be confused with the apparently extremely different “The Outsiders,” which won the recent Tony award for best musical.

Putin’s response to a play — call 911

This week Russian playwright Svetlana Petriychuk and theater director Zhenya Berkovich were sentenced to prison for six years for “justifying terrorism” in their production of Petriychuk’s “Finist, the Brave Falcon.” It’s about a Russian woman who is recruited into ISIS, becomes disillusioned with it, and then returns to Russia where she is jailed as a terrorist. The two theater artists, who had already been in custody for more than a year, and their lawyers contend that the script has an explicitly anti-terrorist message. Their play had already won two Golden Mask Awards, considered the most prestigious Russian arts competition.

And some people claim that theater critics are too brutal…

One is the loneliest number

How many LA-based theater productions did the LA Times review since my last post on June 14? 1

It’s interesting that the Times recently hailed Pasadena Playhouse’s Danny Feldman as “the man who saved L.A. theater” without mentioning that the Times itself appears to be trying to kill L.A. theater through its severe cutbacks in coverage.