Comparing 'Company' and 'Clue'. Alfresco adventures in LA theaters.

'Keely and Du.' 'Dido.' Tom Jacobson's duo. Felder's 'Rachmaninoff and the Tsar'.

Stephen Sondheim was an enthusiastic fan of elaborate games and fictional whodunits.

In 1968, the composer/lyricist and the actor Tony Perkins spent a month planning a Halloween “treasure hunt” in which four teams of five guests each searched for clues throughout Manhattan. Occasionally Sondheim’s hobby crossed into his professional life — he and Perkins wrote a 1973 whodunit movie, “The Last of Sheila.” He and George Furth wrote the non-musical “Getting Away With Murder,” which bombed on Broadway in 1996 (after a 1995 tryout with the title “The Doctor Is Out” at the Old Globe in San Diego).

“The connection between puzzles and detective stories is all about order and solution,” Sondheim said in a New York Times dialogue in 1996 with Anthony Shaffer, whose Tony-winning 1970 mystery-play “Sleuth” briefly had the working title of “Who’s Afraid of Stephen Sondheim?”

“The nice thing” about puzzles and detective stories, Sondheim told Shaffer, “is that there’s a solution and all’s right with the world — as opposed to life.”

Currently LA’s two largest professional legit theaters are occupied by touring productions. The better of the two, at the Pantages in Hollywood, is an audacious gender-flipped revival of the Sondheim/Furth “Company,” the breakthrough “observational” musical (Sondheim himself used this word). It’s about the ironies of “life,” as opposed to “order and solution.”

The lesser of the two, “Clue” at the downtown Ahmanson Theatre, is about “order and solution.” It’s not at all about “life.”

Specifically, “Company” is about the ambivalence that most human beings feel, at least occasionally and sometimes frequently, about their relations with other human beings. It’s structured around an unmarried 35-year-old who has an active social life with friends both married and unmarried — but who remains insecure and undecided about social connections.

In the original “Company,” that central character was a man named Bobby. In Marianne Elliott’s revival, now at the Pantages, Bobby has become Bobbie — a woman turning 35 — and the time frame has shifted several decades into the future, or so it appears. True, a note at the beginning of the script for this version explains that “the narrative is conveyed in a stream of consciousness technique, and time moves both backwards and forwards, encompassing the past, present and future.” OK, but let’s just say that Elliott’s production employs mobile phones as props to an extent that I’ve never seen in any other “Company.”

The new Bobbie, as performed by dynamic Britney Coleman, makes sense for the 21st century. Surely the percentage of women who assume that they’ll be married by 35 has fallen far below the 1970 percentage. But still, women who contemplate parenthood — or at least parenthood involving their own pregnancy — have a more pressing biological deadline than men. Bobbie refers to her “career” at one point, but she doesn’t identify it, which is appropriate in a musical that is laser-focused on ambivalence about personal relationships, not about which job will be the next step in a career.

Among the moments when Bobbie’s friends seize center stage, the most noticeably updated change is in the famously frantic and funny “(Not) Getting Married Today” song, in which an imminent bride, in 1970, hesitates just before the ceremony. Now that bride is a reluctant groom who is about to marry another man. The opening lines of the officiating “church lady” once were “Bless this day, pinnacle of life, husband joined to wife,” but now she warbles this instead: “Bless this day, pinnacle of joy, boy unites with boy.” Sondheim, whose only marriage was to a man, Jeff Romley, at the end of 2017, reportedly expressed his approval of the revised script and saw a preview of the Broadway version before he died in 2021.

He probably would have approved this touring version of the Broadway “Company” as well. Surely his own songs and their performances by Coleman and company still provide the emotional heft for a script that might otherwise seem too heady in its consideration of life’s ironies.

Bunny Christie’s scenic concept is partially inspired by the squares and rectangles of Boris Aronson’s original design, but in conjunction with lighting designer Neil Austin, those geometric forms now are likelier to become darker, more enclosed boxes, emphasizing that the script is about being alone as well as being with “company.” This reminded me of our tendency, especially in the current decade, to spend more time looking at our private screens and less time venturing into public spaces — which of course includes large public spaces such as the Pantages.

I was bedazzled by spending time in the public space created by this new “Company” (which, sorry about that, closes on Sunday). Seldom have the revisions in a classic seemed more apt for the current moment.

On the other hand…

I was bored by the board game-inspired “Clue,” at the Ahmanson. I remember playing “Clue” occasionally in my youth, without recalling if I was even mildly entertained. I know that the game was the source for a 1985 movie, which I had no interest in seeing, but which apparently “inspired” this stage adaptation — written by Sandy Rustin, with “additional material by Hunter Foster and Eric Price, based on the screenplay by Jonathan Lynn.”

I don’t get it. If you’re actively playing a board game, within a few feet of your brain, you’re surely more involved in it than you are if you spend a lot more money to see a scripted adaptation of it on a stage. This is especially true in a venue as big as the 2000-plus-seat Ahmanson, where you’re likely to be far too distant from the stick-figure characters mechanically enacting a whodunit plot. And my seat was closer to the “action” than most. I wonder if games fanatic Stephen Sondheim would have had a different reaction.

Open-air theater

We’re now in the second half of August. Have you seen any professional outdoor theater? True, global warming is busy breaking heat records, but evening performances should provide at least some respite from the daytime temperatures.

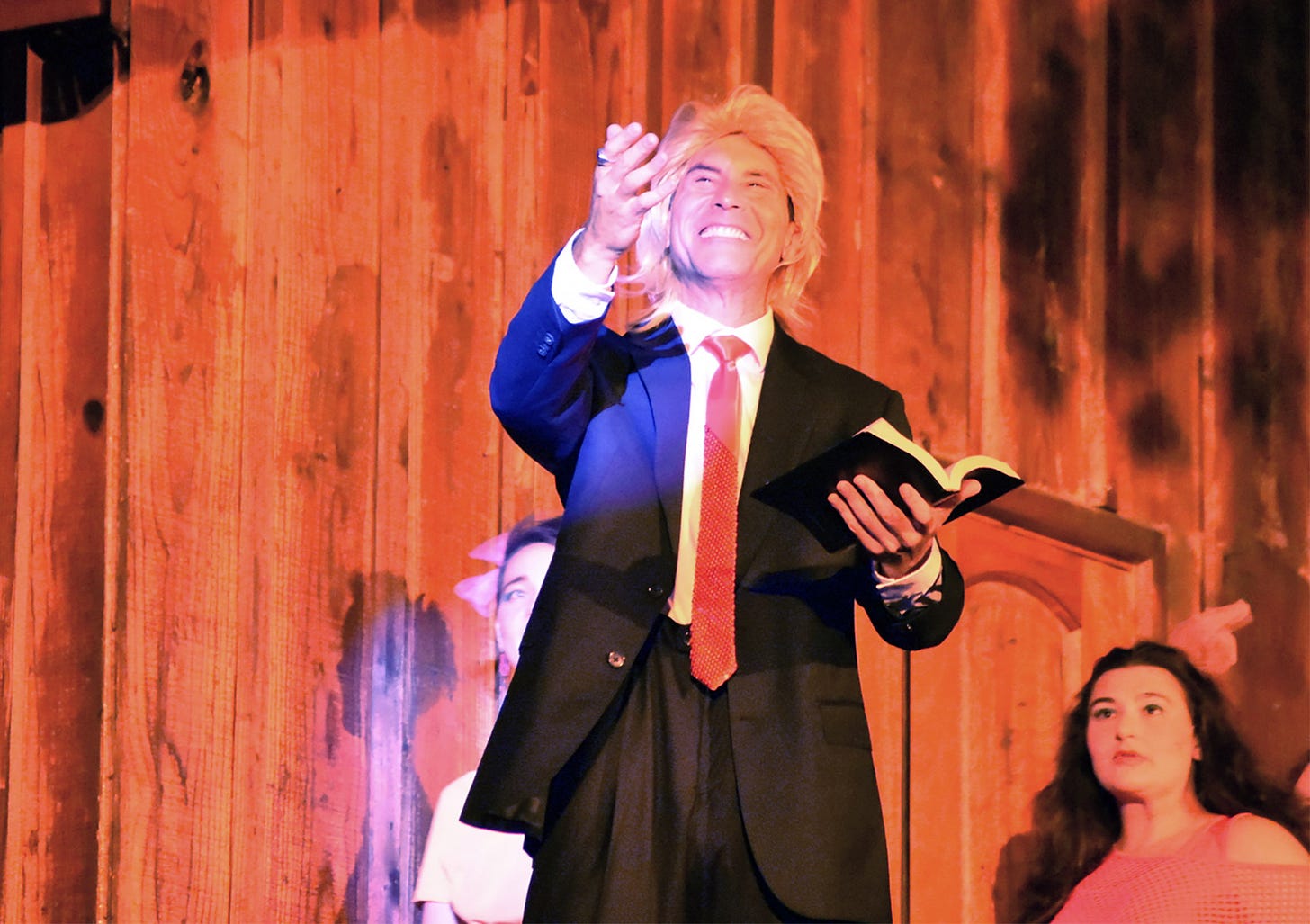

As usual, the Theatricum Botanicum in Topanga offers the greatest variety of options. Four shows have already opened in the company’s repertory season. Of the three I’ve seen, my favorite is “Tartuffe: Born Again.” Translator/adapter Freyda Thomas’ version of the classic Molière comedy features a lascivious Bible-toting con artist in 1980s Louisiana, but still uses rhyming couplets. David De Santos oozes Trumpiness in the title role — he even appears in orangish hair and a red tie near the end. Lynn Robert Berg is superb as his principal dupe. Melora Marshall directed.

Berg is also wonderful in the roles of Captain Hook and Mr. Darling in “Wendy’s Peter Pan,” director Ellen Geer’s new adaptation of the Barrie classic, from the perspective of a grown-up Wendy (Willow Geer) telling her young children about this adventure from her own childhood. Director Geer fluidly shifts our attention to many different places within the Theatricum’s vast canvas. By the way, with its setting in the woods, the Theatricum would surely be ideal, at least scenically, for “Into the Woods.”

Finally, the same director’s staging of Shakespeare’s “Winter’s Tale,” in which Willow Geer stars as Hermione, is quite engaging in the first half, but the lighter second half seems a bit anti-climactic. Then again, perhaps I’m simply getting tired of the second half of the play — I saw an Antaeus production of it earlier this year. That’s probably related to why I usually skip the fourth Theatricum show that has already opened — the annual “Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

Meanwhile, Independent Shakespeare Company — Griffith Park’s resident professional summer troupe, is again occupying a small dell adjacent to its regular space, where (at least theoretically) a permanent stage will eventually be built. This year’s attraction is the Bard’s “As You Like It,” with lively updated musical accompaniment. But I regretfully concluded that I didn’t really like it all that much — and that’s mostly attributable to the dell itself. Even from the perspective of what I supposed were some of the best seats around the dell (those reserved for press), I could barely see a subsidiary stage off to the side through the intervening trees. The sound quality also seemed uneven.

Dear city of LA: The new stage for ISC will be up and running before the Olympics summer of 2028, right? Any chance of raked seating, similar to what the Theatricum has, which would enable better views from the back?

Did Dobbs decision revive ‘Du’?

Abortion has become one of the most contentious issues of the 2024 political campaign. Previously legal nationwide, abortion is now mostly illegal in many states — since the Supreme Court’s reversal of the popular Roe precedent with the much less popular Dobbs decision.

So the times might be right for the return of Jane Martin’s “Keely and Du.” This 1994 play begins after a pregnant woman has been kidnapped by a group of Christian anti-abortion activists. They intend to release her only after it’s too late for her to proceed with an abortion.

Harold Clurman Laboratory Theatre’s revival of the once-highly-touted play, at the Art of Acting Studio in Hollywood, and Bryan Keith’s staging pack a powerful dramatic punch. The script presents the fierce convictions of both sides on this subject in the performances of Sara Eklund as the captive Keely and Sean Spann as the evangelical ringleader.

But a less extreme viewpoint is also represented well by Nike Doukas as Du, a member of the kidnapping group who is assigned to guard Keely in her makeshift cell. Perhaps old enough to have been Keely’s mother, Du is more sympathetic to Keely’s plight than the man who runs the gang. Also appearing briefly is Keely’s ex-husband (Niek Versteeg), who impregnated her in a rape but has since supposedly been converted into acknowledging his guilt.

The venue is dark and somewhat uncomfortable, which is quite appropriate for the atmosphere inside the cell in which it takes place. For the record, I audibly gasped twice near the end of this play, which unfortunately is scheduled to close Saturday.

You might also gasp at least once in the West Coast premiere of “Dido of Idaho,” by Abby Rosebrock, in a savvy in-the-round staging by Abigail Deser at Echo Theater’s Atwater site. This play, too, is about women who are abused, although this form of abuse is very different from what we see in “Keely and Du.” It’s difficult to write about this play without giving away too much of the plot, but Charles McNulty pulled it off quite well in his LA Times review, and I agree with most of his observations.

Speaking of McNulty, I must acknowledge that LA Times coverage of locally-produced theater has improved since I called attention to its shocking shortcomings in May. I reported then that the Times didn’t review any theater in southern California from April 16 to May 17. Looking at a comparable time period from July 16 to today, I see that McNulty reviewed five locally-produced shows plus the LA stops of two touring productions and a “Henry VI” at the Old Globe in San Diego.

That’s progress. Of course, there are still large gaps. How about returning to offering a wider range of shorter opinions about more productions?

How artists dealt with dictators in the ‘30s

Two plays by Tom Jacobson, about dilemmas facing artists during the prelude to World War II, are currently playing in small theaters: “Crevasse” in a Son of Semele co-production with the Victory Theatre, at the Victory in Burbank, and “The Bauhaus Project” in a two-part Open Fist Theatre production in Atwater Village Theatre.

The narratives of both plays are somewhat convoluted, and clarity is further obscured by the use of the same two actors in “Crevasse” to play three roles each and the use of only five actors in “The Bauhaus Project” to play at least three roles each — with two of the “Bauhaus” cast members playing six roles each.

The shorter and the better of the two plays is “Crevasse,” the central part of which is dominated by Jacobson’s depiction of a real-life meeting between the glamorous and pro-Hitler German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl with Walt Disney — in Hollywood. The beginning and the end of the play elevate Riefenstahl’s press agent and his Jewish wife to almost equal prominence. The overall focus sometimes feels diffused.

The actors here, Ann Noble and Leo Marks, are terrific as they seamlessly transfer among their trios of characters in Matthew McCray’s staging.

Note to anyone who might not be recently acquainted with 1930s movies — Jacobson includes many references to Disney animated classics from decades ago, in addition to the films of Riefenstahl. When I recently saw South Pasadena Theatre Workshop’s amusingly ingenious four-actor small-stage version of “The 39 Steps,” directed by Sydney Walsh, I first watched Hitchcock’s 1935 movie version on Amazon Prime, and I’m glad I did.

Jacobson’s concurrent production ‘The Bauhaus Project” is more of a mess. It covers three distinct chapters in the history of the famous architecture and design school, as it switched locations twice and faced increasing political pressure. The subject matter is so detailed that it requires two distinct parts, presented as separate performances. But it’s also burdened by relating this history through the additional overlay of a class of 21st-century art-school students learning about this saga.

If you really want to learn about Bauhaus history in a clearer and more efficient way, might I suggest Wikipedia?

‘Rachmaninoff’ and his sidekick

In “Crevasse” (above), we see Walt Disney giving Leni Riefenstahl a tour of his Hollywood studio. Disney also gave a similar tour to the great Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff. I learned this from Hershey Felder’s “Rachmaninoff and the Tsar,” now playing at Broad Stage in Santa Monica. Felder relates how the composer told Disney in 1942 that he approved of Disney’s 1929 Mickey Mouse cartoon, featuring Rachmaninoff’s famous Prelude in C Sharp Minor. I then found the cartoon in video format here and here.

That was fun, but generally Felder’s latest production rumbles but rambles, never taking off from the runway. As always, he’s a proficient pianist, as he demonstrates in between the spoken parts of the script. In an unscripted questions-and-answers session after the main shows ends, his own engaging personality emerges (and, at least at the performance I saw, he rebutted the claim floated in his script that impostor Anna Anderson might have been the tsar’s daughter Anastasia).

The main innovation of this installment of Felder’s series of stage productions about composers is that it’s not a solo. Another actor, Jonathan Silvestri, is also on stage, playing the second character mentioned in the title — Tsar Nicholas II, who was executed by the Bolsheviks in 1918, after they overthrew the Russian royalty.

But Felder’s play is set at his Beverly Hills home shortly before the composer died of melanoma in 1943, so the “tsar” on the stage is actually the tsar’s spirit, as imagined (and resented) by Rachmaninoff. Dressed in fancy military attire, Silvestri doesn’t look at all ghostly. Instead, he spends too much time simply sitting on a prominently placed bench near the grand piano in Rachmaninoff’s garden — listening to Sergei as if he’s a talk-show host’s sidekick.

By the way, on Felder’s website, he’s selling access to a video of what apparently was an earlier incarnation of this material — “Nicholas, Anna & Sergei,” as recorded from a livestream in 2021. A lot of video imagery also flits across the back of the stage in this current production.